The Mystery of the Wawinet

The pleasure yacht Wawinet sank on September 21, 1942, in Georgian Bay, Ontario, Canada, killing 25 of the 42 on board.

The pleasure yacht Wawinet sank on September 21, 1942, in Georgian Bay, Ontario, Canada. The Wawinet was owned by retired NHL defenseman Bert Corbeau who played for the Montreal Canadiens and the Toronto Maple Leafs. Corbeau was Plant Supervisor at Midland Foundry and Machine Company, of Midland, Ontario, and he was taking the workers out for an evening boating excursion.

Corbeau was an experienced captain and knew the waters and channels very well. The Wawinet suddenly listed over and took on water, just south of Beausoleil Island, and began taking on water. 25 of the 42 men on board, including Corbeau, perished in the accident. To this day, there are still many questions about what caused the Wawinet to sink.

Joining me for this episode are Bert Mason of Penetanguishene, Ontario, and Brien DesRochers of Parkhill, Ontario, whose relatives died on the Wawinet on that day. It remains one of the worse tragedies in Great Lakes History.

This episode is available on YouTube at https://youtu.be/5HpMXDBHEC4.

Written, edited, and produced by Rich Napolitano. Original theme music by Sean Sigfried. All episodes, images, and sources can be found at https://shipwrecksandseadogs.com/blog/2024/12/13/the-mystery-of-the-wawinet/

For AD-FREE listening, join the Officer's Club on Patreon!

Join at https://www.patreon.com.shipwreckspod

Shipwrecks and Sea Dogs Merchandise is available!

https://www.bonfire.com/store/shipwreckspod/

You can support the podcast with a donation of any amount at:

https://www.buymeacoffee.com/shipwreckspod

Join the Into History Network for ad-free access to this and many other fantastic history podcasts!

https://www.intohistory.com/shipwreckspod

Bert Corbeau was an NHL defenceman with the Montreal Canadiens.

Bert Corbeau also played with the Toronto St. Pats.

The Wawinet in its early configuration.

The Wawinet after renovations.

The Thirty Thousand Islands of Georgian Bay.

The Wawinet sank at the southern tip of Beausoleil Island in Georgian Bay.

Bert Corbeau posted this invitation to his workers on the bulleting board of the Midland Foundry and Machine Company.

The Penetanguishene dock where many of the men boarded the Wawinet.

Great-grandfather of Brien DesRochers, Amié Lalamière on board the Wawinet.

Brien DesRochers hoined me as a guest of this episode.

A young Amié Lalamière with his parents.

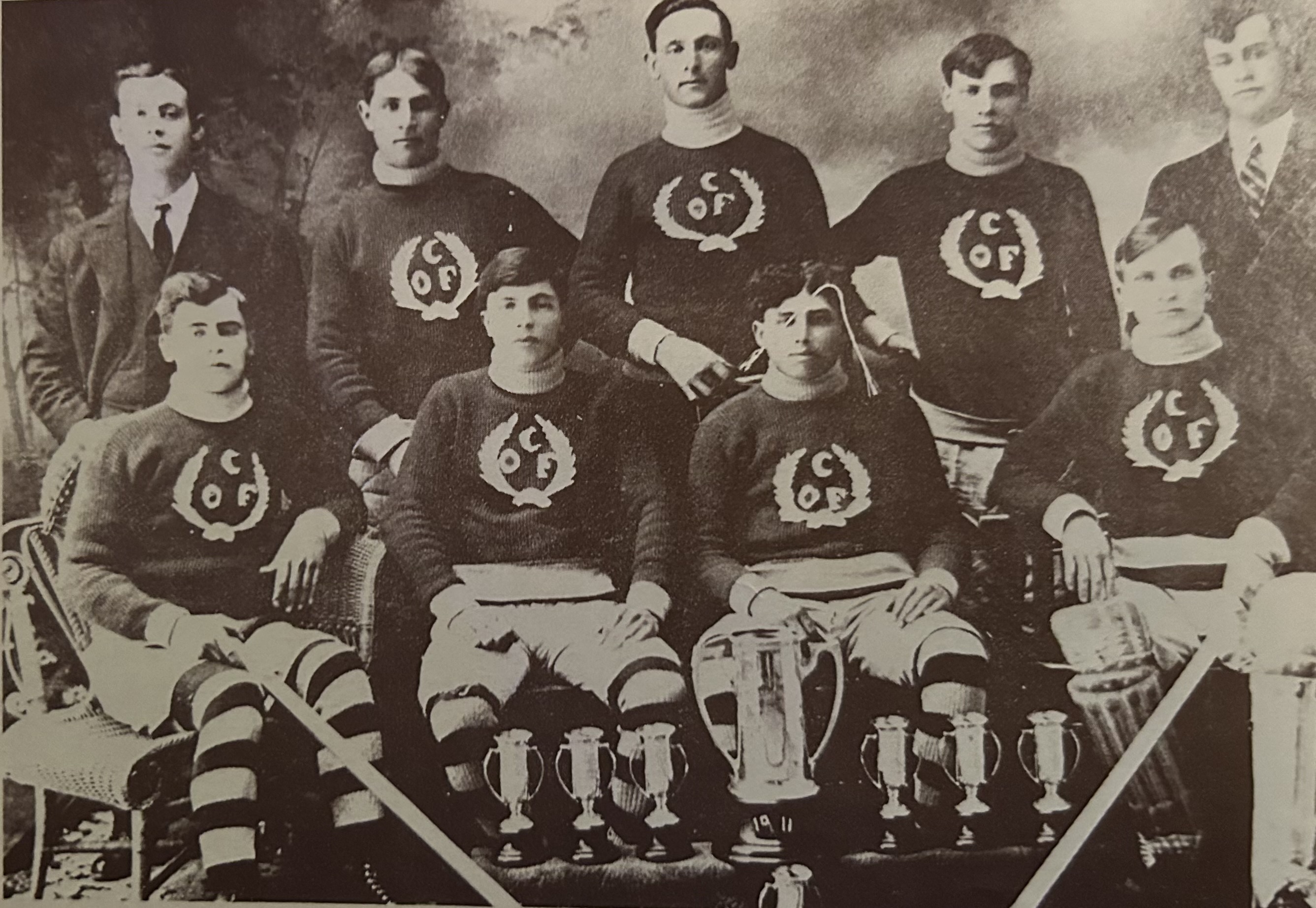

Amié Lalamière and his hockey club. Amie is bottom left.

Amié Lalamière is bottom row, 2nd from the right.

Amié Lalamière holding his young nephew Claude DesRochers, with other family members.

Bert Mason was one of those who did not survive the Wawinet accident.

Bert Mason of Penetanguishene, Ontario is one of my guests for this episode.

He is the grandson of Bert Mason of the Wawinet.

Sources:

Witness Testimony from the Wawinet Investigation

Contemporary Newspaper Articles from 1942

Invititation To Tragedy - The SInking of the Wawinet, by Raymond DesRochers

Remembering the Wawinet, by Jim Withers

Wawinet Steam Yacht, Shipwrecks of Georgian Bay, by Chris Goddard

https://www.divebuddy.com/divesite/356/wawinet-canada/

https://dwhauthor.wordpress.com/2021/07/27/wreckage/

https://www.shotlinediving.com/docs/date/canadian-side-lake-huron/wawinet/

https://www.gettingoldsucks.net/post/remembering-the-wawinet

The Mystery of the Wawinet

Henry DesChamps: [00:00:00] We were telling stories. Some guy had been dancing and everybody was trying to encourage him to give us a step when she took a lurch and everybody went across to one side. She was about to come back when they hit the wall. She gradually went further. I held right to my seat. I got up and came out the door opposite me and went up to the pilot house to see what was the matter.

I found everybody was trying to get up and they were hanging on. Some were scrambling around to get on the far side to bring her back to her position. I reached up and got hold of the top of the door end and swung over to the wall where the wheel is. I swung from the door across and landed on this table where I could get a hold of something and I made my way to the port side of the ship to try and bring her back.

She just came right up and she just settled straight. I leaned over and looked through one of those portholes and the water was over the engine. I figured she wouldn't go any further. She went down very [00:01:00] slowly, and when I saw that the water was in above the engine, I got back to the stern. The lifeboat was there, and a bunch of fellas were yelling.

I said, What's the matter? Why don't you get in the lifeboats? So I got the lifeboat up and pulled the rope up close, and Albert? He got in the boat. He was very nervous and said he couldn't swim, and a few others were yelling they couldn't swim. I told them to get in, so they all climbed in, and I saw there were six in it.

I said, I'll get out. I can swim, so I dove in the lake and swam 20 feet when I flopped over on my back to see how they were getting along. They were getting away, and somebody took a run and jumped off the top of the boat and right into the lifeboat capsizing them. I was told by some of the guys that got ashore that two fellas had got underneath the boat and couldn't get out, and the other fellas held on to the outside.

Rich: This was the personal testimony of Henry Deschamps of Midland, Ontario. Describing his escape from the sinking of the pleasure yacht [00:02:00] Wawinet on September 21st, 1942. The mystery of the Wawinet, today on Shipwrecks and Sea Dogs.

Rich: Hello and welcome to Shipwrecks and Sea Dogs, tales of mishaps, misfortune, and misadventure. I'm your host Rich Napolitano. It is far too often that I come across a truly horrible maritime tragedy that is largely [00:03:00] unknown. Even in the local community surrounding Midland, Ontario, the story of the Wawinet has been mostly forgotten.

The memories of those who were lost and of those who struggled to survive have faded. Keeping these stories alive is not about glamorizing the accidents themselves, but to tell the stories of the people, their experiences, and their circumstances.

On the southern shores of Georgian Bay, in Ontario, Canada, lies the town of Midland. This vibrant, diverse city is the economic hub of North Simcoe County, and is a destination for tourism in the summer months. Originally inhabited by the Huron Wendat Nation, The modern settlement began growing when the Midland Railway chose the location for one of its stops.

During World War II, the Midland Foundry and Machine Company was granted a contract to produce materials for the war effort, and business was booming. Bert Corbeau became the plant superintendent at the foundry in [00:04:00] 1942. From nearby Penitanguishene, Corbeau was a local celebrity, having played 10 seasons as a defenseman in the National Hockey League, and won a Stanley Cup championship with the Montreal Canadiens in 1916.

He was the first NHL player ever to play for the Montreal Canadiens and the Toronto Maple Leafs. Corbeau was known for his tough play on the ice, earning the nickname Pig Iron, and was the first NHL player to accumulate 100 penalty minutes. Corbeau was despised by opposing teams and their fans, and once even had a frozen turnip thrown at him.

He was a menace on the ice. But away from hockey, he was a caring and friendly, hardworking man, and good to his employees, and highly respected in the community. In September of 1942, the workers at Midland Foundry were working 60 hour weeks to complete a large and difficult contract building two sub chasers for the Canadian military.

The project was finished [00:05:00] ahead of schedule, and the president and general manager of the foundry, Elmer Shaw, had promised the workers dinner and drinks. He first suggested the Georgian Hotel, or his personal cottage on Balm Beach. But the men talked it over, and they all wanted a trip on Bert Corbeau's boat.

A relaxing cruise and fishing excursion through the picturesque beauty of Georgian Bay, It was exactly what these hardworking men needed. Better yet, this was to be the beginning of an annual tradition. On September 18, 1942, a Friday, Corbeau posted a printed invitation on the company's bulletin board reading, To all employees, you are invited to attend a stag party aboard my boat on Monday, September 21st at 4pm for a buffet lunch and refreshments.

Come one and all, prizes will be awarded for the best fisherman. Plant Superintendent, B. Corbeau. Corbeau's yacht, the [00:06:00] Wawinet, was originally built in 1904 by Poulsen Ironworks of Toronto for railroad tycoon, Sir William McKenzie. As built, it was 27 meters long, just under 4 meters wide, with a draft of just over 2 meters.

The frame was steel, planked with British Columbia fir, and its keel was made from white oak. The yacht featured a main deck with two deckhouses and a wood staircase down to the cabins of the lower deck. An unusual feature of the Wabanet were its portholes. It had large, square portholes, essentially windows, which could be closed and latched.

There were nine of these on each side, and circular portholes at the bow and stern. Two lifeboats were on board, and gangways were placed on each side of the vessel with wood and brass rails. In 1937, the yacht passed on to Harry Story, a ticket agent with the Northern Navigational Company. During the winter of 1937, the Wawinet [00:07:00] suffered extreme damage from vandalism when it was set on fire.

When Harry Story passed away, Bert Corbeau purchased the yacht from his widow for a total of 372. 50, paid in monthly installments over four years. Corbeau spent about 2, 000 renovating the Wawinet, making changes both to its structure and its propulsion.

Corbeau removed the steam engine, boiler, and firebox, and installed an 8 cylinder gasoline engine.

The keel and frame were replaced with iron, and the hull was repaired, patched, and painted. The old deck houses were removed, and were replaced by a large, modern cabin on the main deck with a lounge, glass windows, pilot house, and a sloping windscreen. Below deck were more cabins including a dining room, kitchen, and engine room.

The original lifeboats were replaced with an 8 foot tender and a 14 foot rowboat. which were towed behind the boat. Corbeau supervised these renovations himself [00:08:00] while the yacht was in dry dock for two years. In July of 1942, Corbeau made the final monthly payment for the yacht and decided to add a second eight cylinder engine for a backup engine and for additional power when needed.

With work completed in the summer of 1942, Corbeau began taking her out, frequently entertaining friends and guests in its spacious cabins. On September 21st, the men from the Midland foundry began gathering at Aimé Lalumière's dock in nearby Penetanguishene, where Bert Corbeau's boat was docked. They arrived in carloads, some of them coming directly from the foundry and were still wearing their work clothes.

Of the 45 workers at the Midland Foundry, 42 of them were in attendance. Bert Mason, of Penetanguishene,

Ontario, is a relative of one of those men.

Bert Mason: My connection is I'm a grandson of one of the men that went down on the Wawinet..

I was named after my grandfather. [00:09:00] It was September the 21st, 1942. It was a Monday, I believe, and then he wanted to paint the house.

And he had been wanting to do that for quite some time. And, uh, rather than go on the boat, you know, he thought, well, that was a good opportunity to, to get a day's work done. But my grandmother coaxed him to go. And the story I get from my mother was that he walked, oh, about a hundred yards from the house, came back, said, you know what?

I'm not going to go. I'll forego this trip. I'm And my grandmother again encouraged him to go and enjoy himself with the boys and, you know, to have a good time with them. And he went a second time and, uh, you know, never did come back.

Rich: Brien DesRochers of Park Hill, Ontario also has a family connection to the Wawinet..

Brien DesRochers: My name is Brien

DesRochers and I am the great grandson of Amie Lalamiere,

who was [00:10:00] one of the 25 men that drowned on the Wawinet.

Um, so the information that I have has been obviously passed on through several generations through my uncle Claude, my uncle Raymond, uh, my dad, um, and my other, uh, uncles and aunt.

Rich: The Wawinet departed Penetang at approximately 4:30 pm and headed north through Penetang Harbor and then east through Severn Sound. Most of the men were on the main deck, or in the lounge in the main cabin, with only a few men down below. General Manager Elmer Shaw had provided sandwiches, hot dogs, and coffee, and Bud Bell brought aboard five cases of beer.

The mood was jovial, but not at all rowdy. The foundry's accountant, Albert Miller, described, It was a very enjoyable party, nothing boisterous at all. Everybody was enjoying the trip. Corbeau took the Wawinet south of Beausoleil Island, allowing William, Rudy, Ellery to take the wheel for a time. When they neared the complicated [00:11:00] network of islands and channels of the 30, 000 islands, Corbeau took over the wheel again.

By all accounts, Corbeau was a master of these waters, and knew every inch of them. Every turn, every shoal, every nuance. Albert Miller praised Corbeau's skills as a captain, saying, Elgin Scott and I were sitting up in the bow, going through the narrow channels, and he is an old waterman. I was sitting with him for the sole purpose of getting a little information about the trip, and he told me that it was amazing how Mr.

Corbeau could get through there so well.

Brien DesRochers: Yeah, he knew them very, very well, um, by all accounts, uh, and you do have to know the waterways up there. It's the 30, 000 Islands. It's part of the Rock Shield. So there's lots of little things you got to look out for and shoals and, and that can change from year to year depending on how the water level is.

So something that was 5 feet below water could [00:12:00] be only 2 feet. if the water level goes down. So, um, but yeah, you definitely need to know your way around. And by all accounts, Bert was very, very good at navigating through the waters.

Rich: Their first stop was at Smooth Rock Island, also called Corbeau's Island, where Bert Corbeau owned a cottage.

They arrived around 6 o'clock p. m. and ate dinner, while some went for a swim and others did a little fishing before heading back out.

It was a calm, moonlit night on the water, and Corbeau navigated the Wawinet through the 30, 000 islands to Honey Harbor. Corbeau docked first at the Royal Hotel, but found the bar was closed, and so they made their way instead to the Delawana Inn. Elmer Shaw and company treasurer J. N. Bicknell each bought a round of drinks for the men.

Their stay at the inn was brief, no more than 30 minutes, and no additional food or drink was brought on board the Wawinet. At approximately 9:20 pm, the men [00:13:00] reboarded the Wawinet as the evening was getting late, and they began heading back to Penetanguishene. Their route took them south into the Sound, and then west toward Penetang.

The weather was mild, but a wind began to blow causing quite a chill in the air. Basil Summers, who was below deck cleaning up and washing dishes with a few others, closed all but one of the portholes in the kitchen cabin to keep out the cold draft. Since it was a calm evening, and there was no concern of water coming in, he did not latch them shut.

Some of the men stayed in the deckhouse, while others donned coats and enjoyed the fresh air outside on the deck. The mood was pleasant, and they settled in for their return trip. The men chatted, sang songs, and one man played a harmonica while others danced an amusing jig. At least one man, Thomas Davidson, was sleeping.

In the wheelhouse with Bert Corbeau were Thomas "Mort" Garrett, Rudy Ellery, Albert Perrault, and Charles [00:14:00] Rankin. At approximately 9:50 pm the Wawinet was just off the southern tip of Beausoleil Island. According to Mort Garrett, Rudy Ellery wished to take the wheel again, as he did on the outbound trip, but Corbeau refused.

Mort Garrett explained what he saw.

Mort Garratt (AI Voice): Rudy Ellery was standing near Bert's rig, arguing with him about taking the wheel and I was standing to Bert's left, on the opposite side of the companionway. Somebody says to Bert, you are off the course, and Bert just grabbed hold of the wheel and gave her one complete turn to port and the boat listed to starboard.

This boat steered opposite. When you turn the wheel to the left, she turned to the right. She did not turn with the wheel.

Rich: As the Wawinet listed to starboard water had begun pouring into the lower deck through the portholes. Some of the portholes were open while others were closed, but not latched. Many of the passengers had been thrown against the starboard side of the boat.[00:15:00]

As the boat continued to tip Corbeau, shouted again, get to the other side, boys, the men, many of whom were holding onto the railing, scrambled over to the port side. Stanley LeClaire made for the far pilot house door across from him and climbed up onto the side rail when he. When he reached the deck, he found himself standing in the water.

About eighteen other men were on the deck, and lined up against the port side holding onto the railing, as Bert Corbeau instructed. As the boat began to return to center, the men left the port side so as not to cause an overcorrection. Leclerc recalled seeing Bert Corbeau standing in the pilot house, with his arms up to the ceiling.

yelling instructions. The Wawinet came back to center, straightened out, and then began settling slowly, never listing to the port side. Corbeau then instructed everyone to stay where they were and that the boat would settle. By this time, enough water had entered the boat through the portholes that the stern section was [00:16:00] underwater.

Basil Summers escaped from below deck by climbing out of a porthole on the higher port side, as the boat was listing. He found himself standing in the water when he got on the deck. In an instant, the relaxing boat trip became dire. Some, such as Elmer Shaw, did not know how to swim. And were terrified of the water.

Charles Rankin, who was on the wheelhouse recalled,

Charles Rankin (AI Voice): "I heard some of the lads shouting to get out and others who were shouting for somebody to toss them a rope because several could not swim. That part was horrible. Bert and I went out of the wheelhouse window, sort of sideways. I pulled off my wind breaker and tread water right where I was."

Rich: Henry Deschamp and Bill Clark spotted Corbeau in the water. He appeared to be struggling, and the two men went in and pulled him out of the water. Corbeau was soaking wet and cold, but still perfectly calm. Men began taking off their shoes and socks and shedding their heavy coats [00:17:00] to avoid being bogged down in the water.

Albert Miller and others climbed on top of the deckhouse, but as the Wawanek continued sinking, they too were forced into the water. Henry Deschamps, as you heard at the top of the episode, helped others board the small lifeboat. Only to see it upturned when someone tried leaping into it. As men began spilling into the frigid water, their natural instincts told them to begin heading for Beausoleil Island.

Seat cushions from the boat were scattered in the water and provided for makeshift flotation for those who could not swim. Stronger swimmers such as Deschamps and Robert Schauble did their best to help those who were struggling. Schaubel testified.

Robert Schaubel (AI Voice): I helped all I could. I passed cushions around and things like that.

There were cushions off the settee. I don't know what kind they were, but they were floating. So I got hold of some of them. And I gave one to Bordeaux, one to McClung, and I don't know who I gave the other one to, but I passed three of them along.

Rich: Stanley [00:18:00] Leclerc began swimming for Beausoleil Island when he caught up to Henry Deschamps.

Deschamps encouraged him, saying, keep going, don't quit now. As the tiring Leclerc continued, Deschamps was Deschamps followed him in, knowing Leclerc had been sick, having just returned to work two days prior. Leclerc finally touched the bottom of the sandbar, and in his excitement, began screaming, then lost his breath.

Deschamps brought him on shore, gave him some clothes, and warmed him up by running up and down the shore. Joseph Parker was able to get away from the Wawinet and began swimming for Beausoleil Island. He later recalled the horrible scene.

Joseph Parker (AI Voice): The shouts and screams for help were terrible. When I looked back, I could see nothing but a struggling mass of people attempting to hold on to each other, or pieces of the wreckage.

Several tried to hold on to me as I was swimming.

Rich: Stuart Cheatham of Brantford, Ontario remembered his own struggle to survive, swimming alongside Rudy Ellery. [00:19:00] They struck out together from the sinking boat for Beausoleil Island, but when Cheatham turned around to check on Ellery, he had vanished.

Cheatham survived. Not by reaching nearby Beausoleil Island, but by swimming over a mile to Present Island. Exhausted and in danger of succumbing to exposure, Cheatham searched the island and found the home of Joe Booth. Mr. Booth provided him with warm clothes, food, and shelter, until he could be taken ashore the following morning.

John Henry Lavigne was just coming up from below deck when the boat went over. Like others, he was thrown against the starboard side. As the Wawinet settled further downward, Lavigne found himself in the water. Recalling.

Henry Lavigne (AI Voice): Henry, he had an oar that he shoved to me, and I had the back of a seat, I gave the oar to Rankin.

I shoved the oar to him, and the seat I gave to somebody else, and I struck off for shore myself. On the way in, I met McLennan, and I took him in as far as shallow [00:20:00] water, and I came out for a friend of mine, Albert. I knew he was a very high strung man, and I went back out to get him. He was hanging on to the boat that was overturned.

Rich: Albert Perrault, who could not swim, made it to shore in the lifeboat, along with Orville McClung, Mort Garrett, and Ken Lowes. Unknown to the men, just meters away on the other side of the Wawinet, was a sandbar they could have stood upon. The 16 men who made it to Beausoleil Island first huddled in the bushes for warmth before finding a cabin belonging to a nearby YMCA camp.

The men huddled in the cabin and started a fire with a canvas tent to keep warm. A group including Joseph Parker felt strong enough to look for help and walked to the home of Peter Taunch, an Ojibwe native who was the caretaker of the National Park on Beausoleil Island. Taunch, with the help of a local priest, provided assistance to the survivors and ferried the men to Honey Harbor the following day.

From [00:21:00] there, they were taken to Port Severn by car, where they phoned authorities in Midland. Elgin Scott, who sat with Albert Miller on the boat, and Bill Clark, who assisted Bert Corbeau, did not survive. One fortunate soul was Lorne Carruthers of Weybridge. Once again, here's Bert Mason.

Bert Mason: His taxi was late, and all he managed to do is get to the town dock, and he saw the Wawinet halfway up the bay, so he missed his opportunity to get on the boat.

And then you can look at my grandfather, who, Probably didn't want to go on the boat, but he did because, you know, he was encouraged to go, so there's irony of, in life, in many instances. Even some of the best swimmers did not make it. My family talked about my grandfather being an excellent swimmer. And I was also told he was, he wasn't a big drinker.

He wasn't. He was very athletic. He [00:22:00] used to amateur box, my father would say. He was in very good 50 years old. Tall man, 6'3 that doesn't mean that you're, you know, you can't be grabbed by someone or you're trying to save and you go down. So there were some that couldn't swim and those who could swim knew that and probably were trying to be of assistance and unfortunately for them it, uh, it was to their demise.

Rich: Aimee Lallemere also did not survive the accident, and Brien Desrochers has some thoughts about what could have happened to his great grandfather.

Brien DesRochers: We were always told that, uh, Aimee was a very good swimmer. Then they told us that a lot of the guys on that trip Didn't even know how to swim. You tend to draw your own conclusions, but I think they could have very well found or, or swam to Beausoleil or one guy made it to present Island as well.

But, uh, when you draw your own conclusion, you have [00:23:00] to think that, you know, they must've been pulled down trying to help somebody. I mean, that, that would be a very hard thing to see somebody you work with or a friend going down and not being able to help them. I mean, I'd hate to be put in that situation.

I didn't find out till later that it is extremely dangerous to try and help somebody, um, especially when you don't have any kind of life saving equipment or flotation device with you, and how dangerous that can be to try and save somebody.

Rich: Bert Corbeau, by all accounts, stayed calm and risked his own safety to help others.

His clothing Beausoleil Island, indicating that he likely made it to shore. and had gone back in the water to continue searching. Charles Rankin, who was in the wheelhouse with Corbeau, later said, When Bert saw what happened, he didn't want to be saved. He was a good host. He loved life, and he took all he could out of it.

The last words heard from Bert Corbeau were, [00:24:00] You boys swim for it. Good luck. Sadly, on the very same night, Bert Corbeau's second cousin Jack Corbeau, Along with two others, were lost during a storm on Lake Michigan.

Despite the terrible tragedy, we can appreciate and admire the incredible acts of selflessness and courage that were exhibited. These included Henry Deschamps, Henry Lavigne, Robert Schaubel, and Bill Clark, as you have heard, and also Gord Eakley of Weybridge, who reportedly assisted several others before drowning himself.

Eakley's wife gave birth to twin boys just two months after his death. [00:25:00] Survivor Ernie Robbins was offered a lifetime job at the Midland Foundry after saving Elmer Shaw. Surely there are more unknown and untold stories of bravery. That we will never know. 25 of the 42 men from the Wawinet perished families were left grieving with little to no income.

It was a tremendous blow for Midland Penang machine in the surrounding area.

Brien DesRochers: Yeah. Well, my great-grandfather had, uh, 11 children he left behind and his wife, so I was reading that, um, there was a hundred, uh, a hundred children that lost their father that day. Amy was, Amy had 11 of those.

Rich: The Midland Foundry lost 42 of its 45 workers, as all but one of the victims, Albert Dix, died.

was a worker at the plant. Dix was an inspector from the John Inglis Company of Toronto and was visiting the Midland Foundry. General Manager Elmer Shaw grieved [00:26:00] of the losses. When he first phoned his wife, he told her, I am alright, but my two best friends are gone. It was terrible. I don't care what happens now.

The two friends Shaw referred to were J. N. Bicknell of Toronto and Buddy Bell of Midland. Shaw quickly turned his attention to the foundry, saying, I'm We have only 16 men left out of a small staff of about 40. But we will build up our organization again as rapidly as possible from the local people. The foundry reopened just three days later.

A fundraiser for the victims families was launched, but results were disappointing, with only about 2, 500 collected within a month of the accident. 1, 500 of that came from the Midland Foundry itself. Search and rescue efforts were hampered by weather and rough seas. The bodies of Bert Corbeau and two others were discovered quickly among the reeds on Beausoleil Island.

By September [00:27:00] 23rd, 22 out of 25 were still missing. People from the surrounding area assisted with the search, including members of the Ojibwe community. Brothers Allen, James, and Donald Clark arrived in Midland on September 23rd to search for their brother, Bill. They brought ropes and hooks to drag the bottom and hired a boat from the local alderman, Lorne Harper.

The brothers found the wreck of the Wawinet quickly and began dragging the area. Throughout the day they searched until finally they found something. It was their brother, Bill. Out of the 22 still missing, they found the one person they were hoping to find. Bert Mason recalls reading about the search for his grandfather.

Bert Mason: I remember seeing the clipping my grandmother had had, um, lost and then missing and, uh, eventually, I think, I think it was the third day when he was, but he was one of the last to be [00:28:00] found.

Rich: The last three victims to be found were Rudy Ellery, Lloyd Strong, and J. N. Bicknell. An inquiry was immediately launched by the Minister of the Department of Transport, C. D. Howe, and he appointed F. S. Slocombe, the supervising examiner of masters and mates, to preside over the witness depositions. Beginning on September 24th, 1942, survivors and relevant witnesses regarding the Wawinet were interviewed. The questions asked of each individual followed the same pattern.

Witnesses were asked about their relationship with Bert Corbeau. The structure and propulsion of the boat, the food and beverages consumed, where they stopped, the location of life saving equipment, and whether the ship seemed unstable prior to the accident. Witness testimony was consistent in some aspects, but conflicting in others.

All confirmed there was beer on board, but by all accounts, nobody was drunk or rowdy in any way. The only [00:29:00] exception, perhaps, was Rudy Ellery. More than one witness remembered seeing him with a pint of gin, but nobody described him as being intoxicated. The testimony from Mort Garrett described Rudy Ellery's argument with Bert Corbeau about steering the wheel.

This appeared to be extremely relevant, but no further questions were asked about it, and of course, neither Corbeau nor Ellery were alive to testify. The blood alcohol level of Bert Corbeau indicated that he had consumed some alcohol, but according to the coroner, he was not intoxicated. Brien Desrochers explains.

Brien DesRochers: Yeah, I'm sure there was definitely some drinking going on. Um, the coroner's, uh, from one of the newspapers that I saw, actually when my uncle tried to get the coroner's inquest, it couldn't be found. But the information that I'm going by is some of the newspaper clippings, is that he was below the limit.

So he, you know, maybe he definitely had a few drinks, but was at the time below the [00:30:00] legal limit. So he definitely, they said that wasn't the cause.

Rich: Witness testimony was consistent with this, that Bert Corbeau was sober. All witnesses that had any knowledge of Corbeau provided nothing but glowing descriptions of his skills as a captain and knowledge of the waters.

Bert Corbeau was a very important figure in town. He was a NHL hockey player who had won a Stanley Cup with the Montreal Canadiens, was a foreman of the Midland Foundry, had the boat. So, you know, I think people generally, even if he was responsible, I don't think they would have said much about him.

Slocombe pushed each witness to find evidence of the Wawinep being unsafe, or possibly having struck something earlier causing damage. Following is the exchange between Slocombe and survivor Kenneth Lowes, an experienced sailor. When she was going through all those narrow channels, did she touch anything? [00:31:00] No.

F.S. Slocombe (AI Voice): You never felt her touch anything?

Kenneth Lowes (AI Voice): No, I never felt her touch anything.

F.S. Slocombe (AI Voice): There was not much vibration on that boat, was there?

Kenneth Lowes (AI Voice): I did not feel her vibrate.

F.S. Slocombe (AI Voice): Not at all?

Kenneth Lowes (AI Voice): No.

Rich: Most of the witnesses testified that there were no problems as the Wawinet navigated through the islands and did not recall any examples of the vessel listing.

However, when Mort Garrett, an experienced sailor, was asked whether the boat listed in the complicated channels, he answered, yes, at one point there is a sharp S turn and the boat listed quite away, but it did not list as quickly as it did when the accident happened. Henry Deschamps added that any boat, regardless of size, would have listed in the sharp turns in the 30, 000 islands.

Slocombe also tried to establish why the Wawinet suddenly listed at the time of the accident. He asked each witness if they felt the boat hit anything or touch anything. But all who were questioned described the moment of the accident [00:32:00] exactly the same. They hit nothing. They felt nothing. The boat just suddenly listed over.

If the Wawinet, in fact, was top heavy and unstable, it might be due to its ballast having been removed. The iron that had been formerly in the ballast had been removed by Corbeaut during remodeling. It is unclear exactly why this was done. Roy French, manager of the Great Lakes Navigation and Machine Company, was familiar with the Wawinet.

In his deposition, French described the Wawinet as a flat bottom boat whose floor of the bottom deck was only 6 inches from the keel. saying there was not enough space to put any amount of ballast in it. Unconfirmed rumors point to Corbeau removing the ballast to make the boat faster, while others have heard the iron was removed to be used for the war effort.

There is no evidence of either of these claims, but we do know for certain that the Wawinet had no built in ballast, and according to French, she was [00:33:00] top heavy.

Brien DesRochers: I think after the addition that they put on, it seems to be the truth that it was tender and it was top heavy, so. Apparently, it's not the most people they had on the boat, so who knows if just that extra bit of turning and maybe the guys kind of fell to one side and brought it over the rest of the way, I don't know, but yeah, that was, that was what they said.

Rich: Life saving equipment was another key focus of Slocombe's. No witnesses recalled seeing life jackets, life belts, or life rings. Basil Summers believed he saw a fire extinguisher in the engine room, and Robert Schaubel testified that somebody told him there were life jackets below deck. They said that there wasn't any life jackets on the boat.

Brien DesRochers: I'm not sure how true that is. He said, he made mention that he was told there was life jackets down, down below by somebody, but Didn't really bother going any further about that. So [00:34:00] just where they drew their conclusions and it's all speculation So it's it's just hard to to lay blame on anything if you don't have concrete proof

Rich: Albert Miller, Henry Deschamps, Joseph Parker, and Thomas Davidson all Testified that they believed at least some of the seat cushions were filled with kapok a common material found in flotation devices at the time Many cushions were seen floating on the surface of the water and were used by the men as flotation devices.

The general consensus from the testimony showed the Wawinet had a trouble free evening up until the accident. Alcohol was consumed, but not in excess, there was no horseplay or rough housing on board, and Bert Corbeau was a capable and skilled captain. For an undetermined reason, The ship listed severely, and suddenly, the yacht was flooded through the portholes, and there was no evidence of life jackets, life belts, or life rings on board.

Many questions were asked about whether or not the [00:35:00] Wawinet was a commercial vessel or a pleasure vessel, and evidence was conflicting about this as well. Corbeau certainly did not receive compensation for the Midland Foundry excursion of September 21st, 1942. Those who knew Corbeau remembered seeing him take previous trips, but believed those trips were all uncompensated as well, as he often entertained visitors to the foundry or other guests.

The determination was important to the inquiry, as commercial vessels and pleasure vessels had different requirements. Slocombe presented his report, stating, Even as a pleasure yacht, there were contraventions of the registration requirements under the Canada Shipping Act of 1934. and of the regulations covering the carrying of certain life saving and firefighting equipment.

Slocombe prepared his findings and provided all evidence to the coroner. Ultimately, the jury of the coroner's investigation issued their verdict. The cause of Bert Corbeau's [00:36:00] death was drowning. A strong recommendation was made for closer supervision and inspection of pleasure craft by the proper department of the federal government.

And lastly, there were many heroic acts exhibited during the accident which should be commended.

After examining all of the evidence and testimony, many questions remain.

Brien DesRochers: I was always told that the, the ship hit the sandbar, but then after reading a lot of the information that my uncle Raymond received, and the Inquisition and stuff, uh, It, it didn't seem like the boat hit the sandbar and then actually sank in about 25 feet of water. So I was always told that, uh, the sandbar was on the other side of the boat and had people just swam across to the other side of the boat, they could have stood [00:37:00] up, which seems to be the case.

One of the, one mention was that, uh, they had to go about 100 or 150 feet to get to the sandbar is what one of the survivors had recorded.

Rich: Did Rudy Ellery cause the wheel to be suddenly turned? Perhaps, but with no corroborating evidence, we just cannot know. Should all of the portholes have been closed and latched?

It was and still is a very common practice for portholes to be open in calm weather, smooth seas, with no obvious threat of water entry. Did Bert Corbeau take the Walwinet off course? According to Mort Garrett, the vessel was not off course. Considering Bert Corbeau's expert knowledge of these waters, it is highly unlikely he was off course.

If what Mort Garrett described is true, and Bert Corbeau turned the wheels suddenly to port, and if the Wawunet was as unstable as Roy French claimed, it just might have caused the vessel to list to starboard. The weight of the [00:38:00] men falling into the starboard side could have made her list further, and faster.

But, that is a lot of speculation, with no clear answers. Why the Wawinet listed over so suddenly remains a mystery.

Brien DesRochers: Just reading all the information, I came up with more questions than answers. And it was always, every time I read it, I always come, seem to come up with more questions. There was a lot of inconsistencies, too, when you, when you actually read all the, the inquest answers.

Rich: Today, the Wawinet lies on about 10 meters of water. and is visited occasionally by amateur divers.

Brien DesRochers: My brother, John, actually dove on the wreck about, uh, he said it's been over 20 years now, but, uh, it sits in about 25 feet of water right now. But at the time with, um, with the bridge and everything on it, um, after the incident happened, they said the very top was only about nine feet underwater.

So they considered it not to [00:39:00] be a hazard, so they didn't do anything. There was talks about salvaging it and bringing it back up. Um, but then that would have been at the cost of, uh, Bert Corbeau, that didn't make it, so it would have fallen on the, the, uh, family. So they didn't, I guess, care to do anything with it.

So it stayed there, they didn't consider it a danger. Uh, when my brother John dove on it, he said that, uh, there was, it was just basically the main hull that was left, that there was no decks, no nothing, nothing. Left on the top either. So he said you could see the square portholes that it had, but that was it.

Rich: The loss of the Wawinet and its 25 victims is one of the worst tragedies in the history of Georgian Bay, and one of the greatest non commercial losses in Great Lakes history. Yet, little is known of the Wawinet, even in the local area, and there are no memorial plaques, markers, or monuments to its victims.

Bert Mason: One thinks of that era. In [00:40:00] that generation, people didn't say a lot. Tight lipped was the norm. My father, when I can recall, never spoke about the incident. My mother did, and I think it probably was very hard. My father was a Great Lakes sailor. I don't know whether the, and I know he was close to his father.

But that's something that he and I never ever discussed. I learned all this from either my mother and a bit from my grandmother. And plus all the newspaper clippings that my grandmother saved that were in the local paper and at the time the Toronto Telegram. The only stories really are the ones that we've read.

Brien DesRochers: And, uh, personally I've never spoken to any survivor of the boat, uh, accident. And, So, as I say, [00:41:00] my information would come from my mother, who would only tell me about my grandfather, not really expressing a desire to go that day.

Actually, my, my uncles and my dad went up to interview Basil Somers, I believe it was.

He was 18 years old when, when the Wawinet accident happened. And so When they saw him, he was close to 80. Um, but even then, my dad was going to videotape him and he wouldn't have any of that. Um, he did allow them to record, but he still seemed a bit guarded about, uh, the information and the information that he provided.

Bert Mason: We want them to be remembered and it's part of the history there, so I think it's important. My sons, until I told them about their great grandfather, I mean, they grew up in this community and I would say that 80 percent of the people didn't know about the [00:42:00] Wawinets tragedy. And I know Brien's uncle and his family and myself.

I felt it was incumbent upon me to make people in our community aware of the town's worst tragedy. I started with the 75th anniversary, and then I would make sure every five years that at least the paper, the newspaper would cover a story or let people know.

Rich: Thanks to the efforts of Bert Mason, Raymond Desrochers, Claude Desrochers, Brien Desrochers, Chris Doddard, and other committed historians, the source materials regarding the Wawinet have not been lost.

Witness depositions, official government correspondence, contemporary and recent newspaper articles, and personal research have been carefully saved and passed down since the time of the accident. These materials that were provided to me proved invaluable in the creation of this episode [00:43:00] and can be found on this episode's page at shipwrecksandseadogs.com Where you will also find the names of all of the victims and survivors. Thank you again to Brien Desrochers and Bert Mason for providing the inspiration to do this episode.

That's going to do it for the mystery of the Wawinet. Thank you for listening. Shipwrecks and Sea Dogs is written, edited, and produced by me, Rich Napolitano. Original theme music is by Sean Siegfried, and you can find him at seansigfried.com. If you would like to support the podcast, you can do so at BuyMeACoffee.com/shipwreckspod, or you can subscribe to the Into History Network.

For ad free listening to this and many other fantastic history podcasts, subscribe at intohistory.com/shipwreckspod. Last but not least, you can buy Shipwrecks and Sea Dogs merchandise at shipwrecksandseadogs.com, get yourself a [00:44:00] shirt, and support the show at the same time. Please join me again next time, but until then, don't forget to wear your life jackets.