The Sinking of RMS Lusitania - Part 1

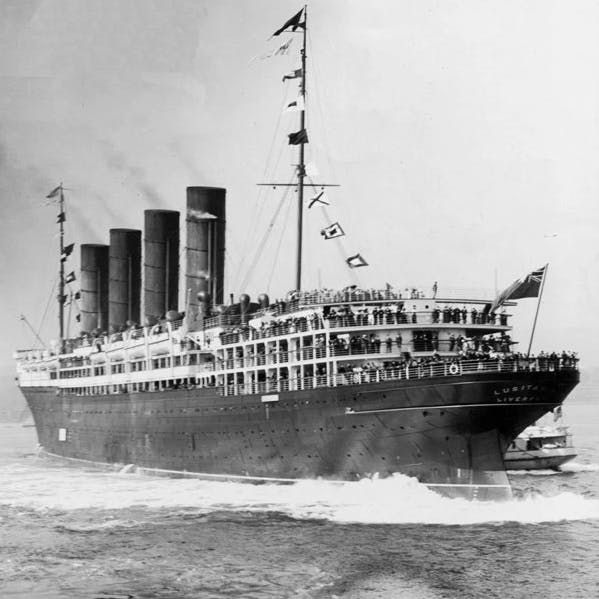

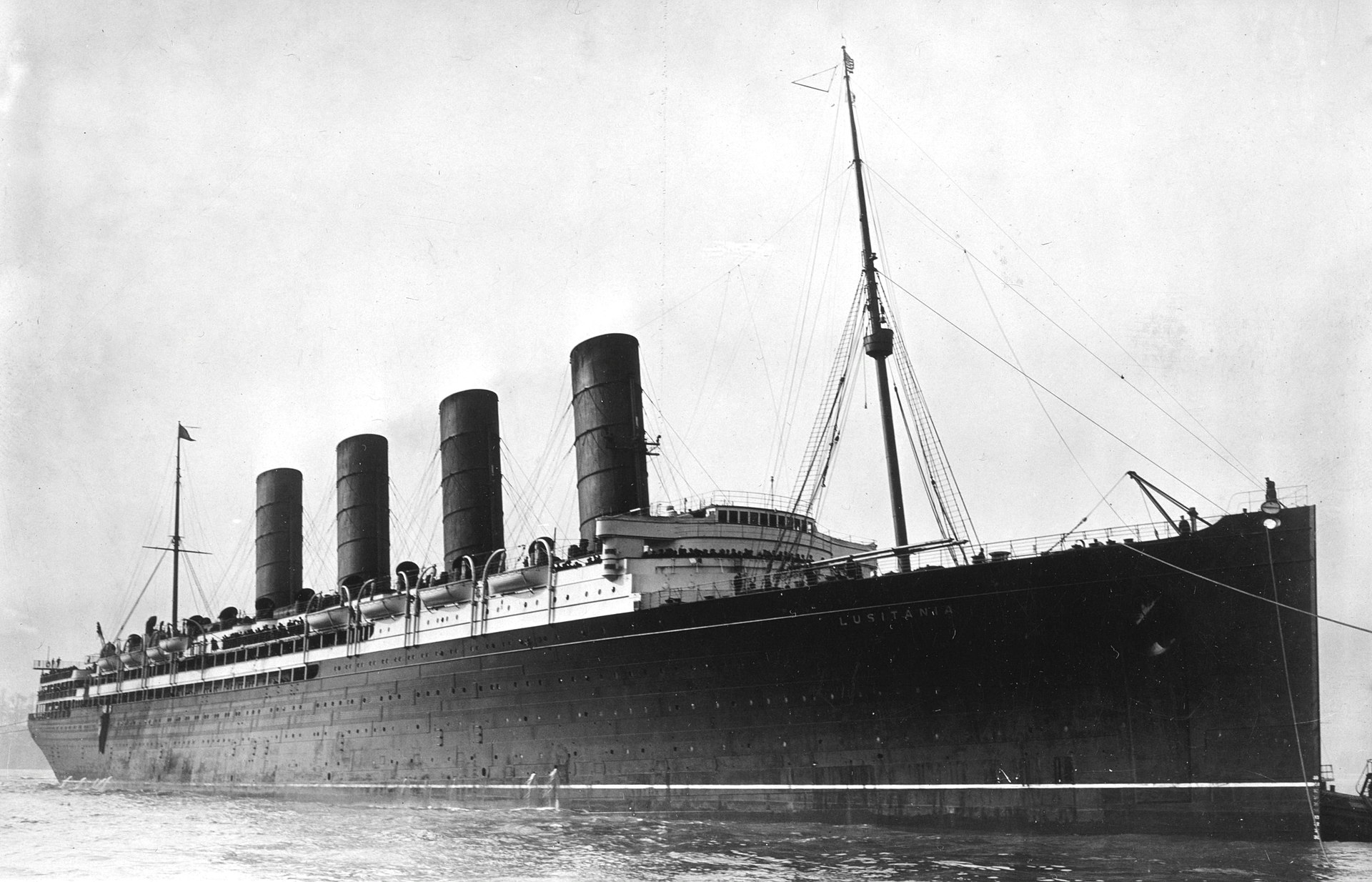

The Lusitania was a luxury passenger ship of the Cunard Line, launched in 1906.

The tragic sinking of the RMS Lusitania in 1915 was a pivotal maritime disaster of World War I that claimed almost 1200 lives after a German U-boat torpedo struck the British ocean liner off the coast of Ireland. Part 1 of this 2 part series discusses the history of the Lusitiania as a luxury liner, political tensions as World War 1 began, and the events of the Lustiania's final voyage up until it was struck by a torpedo.

Written, edited, and produced by Rich Napolitano. All episodes can be found at https://www.shipwrecksandseadogs.com.

Original theme music by Sean Sigfried.

Listen AD-FREE by becoming an Officer's Club Member ! Join at https://www.patreon.com/shipwreckspod

Shipwrecks and Sea Dogs Merchandise is available! https://shop.shipwrecksandseadogs.com

You can support the podcast with a donation of any amount at: https://buymeacoffee.com/shipwreckspod

Join the Into History Network for ad-free access to this and many other fantastic history podcasts! https://www.intohistory.com/shipwreckspod

Follow Shipwrecks and Sea Dogs

- Subscribe on YouTube

- Follow on BlueSky

- Follow on Threads

- Follow on Instagram

- Follow on Facebook

- Follow on TikTok

Learn more about your ad choices. Visit megaphone.fm/adchoices

Words of Annie Elizabeth Adams:

“My husband and I were married in Washington on April 5,” she said. “We were coming to London to make it our home. He did not wish to sail on the Lusitania because of the threats of the German Embassy, but some of my relatives are Cunard officials and I have always been a confirmed Cunarder, so I insisted on the Lusitania. On the night before we were torpedoed, something prompted my husband to try on the lifebelts. We got them down from the top of the wardrobe, and after putting them on, left them under the berths.

When the shock came we were both in the writing room on the top deck. I knew the ship was doomed, but my husband was just as sure she could not sink. However, we went down to the stateroom, got our life-belts and ran back to the top deck, preservers in hand. The ship was listing so that it was very difficult to walk. On two occasions while ascending the stairs my husband was struck and knocked down. On deck he wanted to stand and listen, but I kept in the lead and helped him climb the sloping deck and reach the rail on the higher side.

Here we saw a boat ready to be lowered. Someone shouted, ‘Women first,’ but I refused to get in, insisting on staying with my husband. He seemed dazed and almost unconscious. I put a life preserver on him and then put on my own. In the meantime the captain had ordered the boats not to be lowered. A bosun, standing beside me on the deck, said, ‘We’re resting on the bottom. We cannot sink.’ This statement calmed most of those about us.

My husband sat down on a collapsible boat. He seemed unable to stand. There we remained for several minutes, holding on to the rail in order to keep from sliding down the inclined deck. Suddenly I saw a great wave come over the bow and instantly my husband and all of us were engulfed. As the ship sank, I found I was being carried down under a life-boat.

It got pitch black. Then suddenly it became lighter. The dark blue turned to light blue and then I was in the sunshine – afloat, though I could not swim. Finally I caught hold of a piece of wood and held on. After a time, a raft carrying twenty men and one woman floated by. I begged the men to help me aboard, but they did not want to, and it was only when the woman upbraided them that one of the men dragged me on the raft.

There was something wrong with the raft, as it kept capsizing time and time again. Each time it was less buoyant and almost every time it overturned one or more of the poor wretches would disappear. Finally the other woman went down. I made use of my gymnastic knowledge, and as the raft turned I crawled hand over hand, always managing to stay on it.

Finally, only six of us were left and then the raft sank from under us and we were left alone in the water. Altogether it was three hours and a half before a torpedo boat came. I saw it in the distance, but was so exhausted and numb with the cold by then that I lost consciousness and knew no more until I recovered aboard the torpedo boat.

One of the heroes whose name has not been mentioned was aboard that boat. He was Second Officer Burrowes. After the doctor had given me up for dead he continued to work on me, and finally succeeded in reviving me. He did as much for others as well, but he refused to accept even thanks.”

Rich Napolitano:

These words are from Mrs. Annie Elizabeth Adams, a survivor from the RMS Lusitania. Hers is just one of many similar stories of shock, survival, and grief, from May 7th, 1915.

Hello and welcome to Shipwrecks and Sea Dogs, tales of mishaps, misfortune, and misadventure. The sinking of RMS Lusitania, in the midst of World War 1, is one of the most infamous events in history. The attack on the Cunard passenger liner by German submarine U-20 in 1915 killed over 1000 civilians and crew, and sparked international outrage. The British government called the Germans war criminals; conspiracy theories raged, and anti-German sentiment heated up in the officially neutral United States. From its celebrated launch until its demise, Lusitania was one of the most celebrated luxury liners of its time, and its destruction had significant global impact.

Transatlantic passenger service in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was dominated by just a handful of companies, including the three British behemoths, Cunard, White Star, and the Inman Line. The Inman Line was a pioneer in the passenger liner industry, and competed heavily with Cunard for the New York/Liverpool route. It was absorbed into the Philadelphia based American Line in 1893, but remained a major player for several more decades. The popular Cunard Line was known for its reliability, speed, and safety. RMS Campania won the Blue Riband in 1893, and RMS Lucania won it again for Cunard in 1894. The White Star Line was popular for its luxurious ships, such as the Teutonic, Majestic, and Oceanic, and competed not only for transatlantic routes, but for service to the Pacific and Indian Oceans as well. The German companies of The Hamburg Line and Norddeutscher Lloyd also provided fierce competition, especially with the transportation of immigrants.

By 1900, Cunard was falling behind its competitors in size, speed, and comfort. Ships such as The Hamburg Line’s Deutschland, and the Norddeutscher Lloyd's 4-funneled Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse, out-classed Cunard’s ships. Meanwhile, American tycoon J.P. Morgan had formed the conglomerate International Mercantile Marine, purchased the White Star Line, and had controlling interest in all other North Atlantic passenger lines except Cunard. The only remaining transatlantic British shipping line was Cunard, and this would be a huge problem for the United Kingdom if war broke out.

To meet this challenge, Chairman of Cunard, James Burns, the 3rd Baron of Inverclyde, sought help from the British government under Prime Minister Arthur Balfour. Positioned as a plea to keep transatlantic shipping from being dominated by the Germans and Americans, Burns was able to secure a loan of £2.6 million. Cunard also received a yearly subsidy of £75,000 and a £68,000 contract to carry the Royal Mail. This influx of cash allowed Cunard to plan the construction of two modern ships that could compete with White Star, NDL, and Hamburg Lines. In return, the ships would be built to the specifications provided by the Admiralty, which would allow them to be used by the Royal Navy in times of war. Cunard planned to build two new ships, the Mauretania and the Lusitania.

A design committee was formed by Cunard to meet all the specifications required by the Admiralty, and to develop fast, luxurious, comfortable, and modern ships. Construction began on the 16th of June 1904, at John Brown and Company shipyard, hull number 367, in Clydebank, Scotland. Mauretania was built concurrently at Swan Hunter shipyard in Wellsend, England. The ships, as yet unnamed, were referred to as the Scottish Ship and the English Ship by Cunard.

Unlike typical ship construction at the time, Lusitania was built starting at the bow, and moved steadily toward the stern, instead of starting at both ends and meeting at the middle. But this was only because the specs for the ship’s engines and stern section had not yet been approved. Cunard Chairman Lord Inverclyde hammered in the first rivet himself. The unprecedented size of Lusitania required the shipyard to add reinforcement piles, install railway tracks, and reconfigure the slip to launch at the intersection of the Clyde and the River Cart to launch diagonally; her length of 787 feet was longer than the River Clyde was wide.

Lusitania was launched at 12:30 p.m. on the 7th of June 1906. Princess Louise was invited to christen the new ship, but was unable to attend. Instead, Lady Mary Inverclyde did the christening. Her husband, Cunard Chairman Lord Inverclyde had passed away 8 months prior.

Thousands of invited guests and spectators watched and cheered as the enormous ship slid into the river. Tugboats then guided her to her berth at Tail o’ the Bank at Gourock, where Lusitania would be fitted out with its four funnels and superstructure, and its interior design completed.

At 144 feet in height from its keel to the tops of its funnels, and just under 88 feet wide, the Lusitania was an awe-inspiring sight. Cunard invited VIP guests on board for a 2-day shakedown cruise, while running at speeds of 15, 18, and 21 knots; below its top speed. After this initial test, the guests departed, and full trials began. Four voyages were made between the Corsewall Light at Kirkcolm, Scotland,and the Longships Light off Cornwall. The Lusitania had to achieve a speed of at least 24 knots, according to the Admiralty’s specs, or Cunard would be fined £10,000 for every 1/10 of a knot under this requirement. But its four Parsons turbines and 25 boilers powered the ship’s four propellers to a record speed of 26.4 knots during trials. In August of 1907 it reached 26.7 knots. However, such high speed caused a terrible vibration in the 2nd class cabins at the stern. Additional reinforcements and a redesign of the 2nd class cabins partially corrected this problem, but a vibration in the stern persisted throughout the ship’s lifetime. Her speed earned her the nickname of “Greyhound of the Atlantic.”

With her fitting out complete, and trials successful, RMS Lusitania departed on her maiden voyage at 9 p.m. on the 7th of September 1907. She departed Liverpool, England under the command of Commodore James Watt, with hundreds of thousands of people gathered to see her off. The Lusitania was bound for New York, after a stop in Queenstown, Ireland, which is today the port town of Cobh (Cove).

The Lusitania was a luxurious ship for her time, and could accommodate 563 Saloon Class (First class) passengers, 464 second class passengers, and 1,138 third class passengers across six decks. Scottish architect James Miller was chosen to decorate the ship, and he used a theme of white plasterwork and gold leaf to create a light and roomy feel. The ship featured electric lights, wireless telegraph, and a grand staircase that surrounded electric gilded cage elevators, or lifts.

First class accommodations were located in the middle of the ship, between the first and fourth funnels, and took up the 5 uppermost decks, A through E. The first class lounge featured Georgian style architecture, mahogany panels, high marble fireplaces at each end, a vaulted skylight and stained glass windows. The grand dining saloon was the jewel of the ship, adorned with white plaster, gold leaf, mahogany panels, Corinthian columns, a domed ceiling, all inspired by the neoclassical style of Louis XVI. First class passengers also enjoyed a reading and writing room for the women, a lounge and music room, and the Verandah Café which could be opened up during nice weather. Her elegance and luxury matched that of even the finest hotels.

Second class accommodations located at the stern of the ship were not quite as glamorous or as large, but still very nicely appointed, and certainly comfortable. There was a public lounge, and a reading library reserved for the women. 3rd class accommodations were plain, but spacious and comfortable. Most passenger ships at the time had large, dormitory style berths for third class guests, but Lusitania was designed with more private spaces of 2, 4, 6, and 8-person berths. Each level of accommodation had its own dining saloon, plus a smoking room reserved for men only. Although each class of passengers had their own public spaces, first, second, and third class passengers were kept completely separate from each other, as was usual for the time.

Lusitania was the largest passenger ship in service when she made her maiden voyage. This was a brief distinction, however, as her sister ship Mauretania was 3 feet longer, and made her maiden voyage two months later. Lusitania arrived in New York on Friday, September 13th, 1907, to an excited crowd of more than 200,000 people lining New York harbor, waiting to get a glimpse at this new marvel. More than one hundred horse-drawn carriages lined up waiting to carry Lusitania’s passengers from Cunard’s Pier 54. During its one week stopover in New York, guided tours were open to the public. Author Mark Twain toured the Lusitania, and remarked afterward, “I guess I’ll have to tell Noah about it when I see him.”

After a successful return voyage to Liverpool, Lusitania departed Liverpool for her 2nd transatlantic roundtrip voyage on October 6th and arrived in New York on October 11th. She set a new speed record of 24 knots, taking only 4 days, 19 hours, and 52 minutes, earning her the Blue Riband for the westbound crossing. The return trip to Liverpool was another record, and earned the eastbound Blue Riband as well, with a time of 4 days, 22 hours, and 53 minutes. Lusitania was the first ship ever to cross the Atlantic in less than five days. Her sister ship, the Mauretania was slightly faster and would go on to break both of Lusitania’s records.

The launch of Lusitania and Mauretania caused concern for the White Star Line’s chairman, Joseph Bruce Ismay. The speed and reliability of Cunard’s liners were a threat, and prompted White Star to begin designing its new Olympic class liners. These were the Olympic, Britannic, and Titanic. The first of these, Olympic, did not enter service until 1911.

In 1909, Lusitania’s four 3-bladed propellers were replaced with four-bladed models, which were 6 feet wider in diameter. This not only increased her speed to be virtually the same as Mauretania’s, but also helped reduce the vibration at the stern. On January 10, 1910, Lusitania was two days into a voyage from Liverpool to New York when it encountered a rogue wave. The 75 foot wall of water crashed into the bow of the ship, and into the bridge. Its forecastle was damaged, the windows were smashed, and the bridge was permanently shifted a few inches aft. Nevertheless, the Lusitania persevered, and continued on to New York on schedule.

Lusitania, along with many other ships, participated in the two-week long Hudson-Fulton Celebration in 1909, honoring the 300th anniversary of Henry Hudson sailing up the Hudson River and the 100th anniversary of Robert Fulton’s steamboat, the Clermont.

With Cunard now competing with the larger and more luxurious White Star liners, in May of 1914, Cunard added another ship to its fleet, the Aquitania. By this time, RMS Titanic had already been lost, but RMS Olympic and RMS Britannic were providing elegant, upscale service. Aquitania was a bigger, bulkier, and slower ship than Lusitania and Mauretania, but it emphasized luxury over speed.

1914 also brought massive changes not only for Cunard, but to the entire world. The outbreak of World War 1, also referred to as The Great War, officially began on the 28th of July, 1914, when the Austro-Hungarian Empire invaded Serbia. This was in direct response to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, earlier that same day. War had been simmering for years in Europe and the causes of World War 1 are far too complex for this episode. However, the opposing alliances are important to understand. On one side were the Central Powers of the German Empire, Austro-Hungarian Empire, and the Ottoman Empire. On the other, were the Allied Powers, also called the Entente, of the United Kingdom, France, and Russia. Russia would later drop out of the war in 1917 as a result of the October Revolution and its own civil war.

Cunard’s loan from the British government came with the agreement that the Lusitania and Mauretania could be requisitioned by the Admiralty should war arise. Classified as Armed Merchant Cruisers, they were painted a dull grey to make them less conspicuous. However, these ships required an incredible amount of coal to power their boilers; coal that was short in supply and badly needed elsewhere. Therefore, the Admiralty chose not to put them into service in the war after all. Cunard returned the Lusitania to commercial service, while Mauretania and Aquitania were laid up in Liverpool for a time.

Transatlantic travel dropped off with the outbreak of war, but there was still enough business to keep Lusitania in service. She resumed her normal route, but with a few changes. To help conserve coal, boiler room #4 was shut down. This reduced the ship’s average speed to 21 knots, but it was still the fastest commercial ship afloat. It was also forced to operate with a reduced crew, as many men were serving in the war., and she was repainted to her usual colors, with orange-red funnels, brass lettering, and a gold stripe surrounding her superstructure.

The British Royal Navy far outnumbered the German navy, and stopped and searched all ships, including neutral ships. In November of 1914, the British government announced the North Sea and English channel were a military zone, and they would sink any German ships found in those waters. A British blockade prevented supplies and food from reaching Germany, which starved its economy, and its people. For their own survival, Germany needed to open shipping lanes. Meanwhile, the ability for war materials and food supplies to reach the British Isles was critical, and Atlantic shipping lanes remained relatively safe at the start of the war.

But Germany had developed and deployed what would become a deadly weapon: the Unterseeboat, or U-boat. Up until this time, submarines had predominantly been used for coastal defense and reconnaissance, and not as an attack vehicle. While British intelligence knew of the new German submarines, they were not seen as much of a threat. That is, until German submarine U-9 sank three British warships on September 22, 1914, killing 1,459 people. From that moment, the U-boat was feared and respected.

Submarines were not new technology in 1914. The first submarine ever used to sink an enemy ship was the H.L. Hunley in 1864, during the American Civil War. You can hear that story in episode 76 of Shipwrecks and Sea Dogs.

A loose set of Naval rules called the “Cruiser Laws” was adhered to by most nations at the start of World War 1. Over 300 years of various rules of engagement culminated in the 1909 London Declaration concerning the Laws of Naval War. This was signed by the primary European powers, the United States, and the Empire of Japan. Although the treaty was never ratified, all participants abided by its terms, at least, for a time.

This set of regulations outlined a procedure for an attacking ship to fire a warning shot at merchant vessels, indicating intention to board. The merchant vessel was expected to stop and allow the attacking party to board the ship and inspect it for war materials or other contraband. The attacker then would allow all crew and passengers to safely evacuate the ship. The merchant vessel could then be kept as a prize, but more commonly, it was destroyed.

By the end of January 1915, German u-boats had sunk 23 ships, totaling 123,000 tons of shipping. The largest was the French battleship, Jean Bart, on December 21, 1914. On the 4th of February 1915, Germany declared the waters around the British Isles to be a warzone, and operated under the terms of the Cruiser Laws.

When the declaration was issued, Lusitania was on voyage from New York to Liverpool. While off the coast of southern Ireland, Captain Daniel Dow, fearing German U-Boats, raised the American flag over the Lusitania, masquerading as a neutral ship. This was a controversial decision, and caused political fallout. On February 10th, 1915, United States Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan sent a telegram to the US Ambassador in London, Walter Page, reading…

The Department has been advised of the declaration of the German Admiralty on February fourth, indicating that the British Government had on January 31 explicitly authorized the use of neutral flags on British merchant vessels presumably for the purpose of avoiding recognition by German naval forces. The Department’s attention has also been directed to reports in the press that the captain of the Lusitania, acting upon orders or information received from the British authorities, raised the American flag as his vessel approached the British coasts, in order to escape anticipated attacks by German submarines. To-day’s press reports also contain an alleged official statement of the Foreign Office defending the use of the flag of a neutral country by a belligerent vessel in order to escape capture or attack by an enemy.

US President Woodrow Wilson warned that British ships flying neutral flags needlessly endangered neutral shipping, while doing nothing to prevent British ships from being attacked. Germany was outraged as well, labeling such actions as illegal.

Two days later, on February 12th, Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill wrote a memo to Walter Runciman, the president of the Board of Trade. In part, it reads, “It is most important to attract neutral shipping to our shores in the hope especially of embroiling the United States with Germany . . . . For our part we want the traffic — the more the better; and if some of it gets into trouble, better still.”

Churchill further ordered British merchant vessels not to stop for German U-boats, and to make an attempt to sink them, presumably by ramming them. He also threatened court martial for any British crew that stopped and complied with the Cruiser Laws. In response, Germany issued a warning that all Allied ships sighted within the war zone would be sunk without warning starting February 18th, and this included passenger and merchant ships of its enemies. Any neutral ships would fall under the terms of the Cruiser Laws.

Churchill again raised the stakes by ordering British merchant vessels to arm themselves, and to fire on any German U-Boats that attempted to approach. This war of words intensified the arms race over maritime supremacy.

The Lusitania was a valuable target for German U-boats, despite it being a passenger ship. On March 4th, 1915, U-27 under command of Kaptainleutnant Bernhard Wegener, was lying in wait off the coast of Liverpool. Wegener believed the ship would arrive on the 4th, and he held off firing on other ships, so as not to scare away his big prize. He patiently waited through March 5th before returning to Germany, and the Lusitania arrived safely the following day.

A month later, the Lusitania arrived at Liverpool after another eastbound voyage. Captain Dow then reported to be very ill and went on sick leave. He was almost certainly needing relief from the stress of sailing through an active war zone. Captain William Thomas Turner was chosen to temporarily take his place. Turner had previously served as captain of the Lusitania, as well as the Mauretania and Aquitania. On April 17th, the Lusitania departed Liverpool for New York, for her 201st crossing of the Atlantic, and arrived safely in New York a week later.

Following her arrival, more changes were made to the Lusitania. Her superstructure was again painted a dull gray, and her funnels were painted black. New instructions for avoiding u-boats were received as well as orders to not fly any flags at all within the designated war zone. But no further attempts were made to disguise her, as the ship’s profile was very well known, especially her four funnels.

The escalating tensions and increased u-boat activity caused German-Americans in New York to worry about U-Boats attacking ships and killing American citizens. Knowing this would cause anti-German sentiment, the German embassy published a warning in 50 US newspapers across the country, warning American passengers not to travel on the Lusitania’s next trip, scheduled to leave May 1. The text of the warning read:

NOTICE!

Travellers intending to embark on the Atlantic voyage are reminded that a state of war exists between Germany and her allies and Great Britain and her allies; that the zone of war includes the waters adjacent to the British Isles; that, in accordance with formal notice given by the Imperial German Government, vessels flying the flag of Great Britain, or any of her allies, are liable to destruction in those waters and that travellers sailing in the war zone on the ships of Great Britain or her allies do so at their own risk.

IMPERIAL GERMAN EMBASSY

Washington, D.C. 22nd April 1915

While the advertisement was placed on April 22nd, it was not published until May 1 - the very day Lusitania departed New York. In many of the newspapers, the German warning was printed directly adjacent to a Cunard advertisement for the Lusitania. In the New York Times, the warning was printed just a few lines under the Lusitania advertisement, on page 19, wedged between ads from other passenger liners. Cunard representative Charles Sumner and Captain Turner dismissed the embassy’s warning as nonsense. Turner told reporters that the Lusitania could outrun any u-boat, and all the talk about torpedoes was the “greatest joke.” Mysteriously, approximately 50 telegrams were sent to the more affluent passengers booked for the Lusitania’s next voyage, such as millionaire Alfred Vanderbilt, and Broadway producer Charles Frohman, warning against boarding the Lusitania. These curious telegrams were also largely dismissed. Very few believed the Germans would dare sink the Lusitania, packed with innocent civilians.

Second class passengers Theodore and Belle Naish boarded the Lusitania on May 1st, and were given a newspaper showing the warning from the German embassy. Mrs. Naish later recalled her husband’s words to her, “We will not worry. No reputable newspaper would accept an advertisement of that Cunard Line size and in it put another in direct opposition. If that were official, the notice would have been posted in glaring signs, and each American passenger would have had warning sent and delivered before boarding the vessel.”

Atlantic crossings had been tense since the outbreak of war, and certainly there was trepidation. There were some last minute cancellations, such as famous Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini, who cut his time short in New York and boarded the Italian liner Duca degli Abruzzi to return to Europe. Broadway composer Jerome Kern overslept when his alarm clock failed to ring, and he missed the departure. Dancer Isadora Duncan chose to take the Italian liner Dante Alighieri a week after the Lusitania departed. William Morris, founder of the famous talent agency, canceled his trip on the Lusitania at the last minute to tend to other business matters. The fortunate Morris also canceled his voyage on the Titanic 3 years earlier.

However, the cancellations for the Lusitania’s May 1st voyage were no more than usual. Perhaps it was all bravado; showing courage in the face of true fear. Cunard continued to make assurances of the ship’s safety, and that escort vessels would protect her.

Lusitania was scheduled to depart New York at 10:00 am on May 1st. However, the Cunard ship Cameronia had just been requisitioned by the Admiralty, and its 41 passengers had to be transferred to the Lusitania. As passengers waited to depart, they wondered if the delay meant there was a problem, or perhaps the Captain or Cunard itself had decided to take the warning seriously.

Finally at 12:20 pm, with a light rain falling, the Lusitania departed Pier 54, with 1,264 passengers and 693 crew. Shortly after departure, 3 German stowaways were discovered in the port-side steward pantry. Staff Captain James Anderson had the men arrested and placed in custody below decks. The men were interrogated by undercover Detective William Pierpont of the Liverpool Police, with the aid of translator Adolph Pederson, but they refused to answer any questions. The only statement Pierpont could get out of them was that they would, “show Winston Churchill how to trim his navy.” The stowaways were reportedly carrying photographic equipment, and were determined to be German spies.

As the Lusitania chugged across the Atlantic, some passengers became frustrated by the lack of any lifebelt instructions or lifeboat drills. Second class passenger Ian Holbourne became vocal about the lack of safety drills, so much so that he was scolded by the Captain on May 4th, and ordered to cease, as he was upsetting the passengers. Saloon passenger George Kessler complained directly to Captain Turner about the need for lifeboat drills, and was told, in no uncertain terms, to stop interfering.

On May 6, the Lusitania entered the waters of the war zone. Captain Turner ordered a ship-wide blackout, covered the skylights, ordered additional lookouts, had the lifeboats swung out, and ordered no smoking outside on the decks. To the surprise of the captain and crew, no escort vessel was present to greet them.

At 11:50 PM, Lusitania received a submarine warning from the Admiralty, but Captain Turner found it insufficient, and lacking any real actionable details. From the time Lusitania departed New York, until May 7, German u-boats had sunk 23 ships off the coast of southern Ireland, including SS Candidate on May 6th. None of those sinkings were reported to the Lusitania.

As heavy fog set in at 6:00 AM on May 7th, extra lookouts were posted, additional soundings were taken, and Captain Turner slowed to 18 knots. He also regularly sounded the ship’s foghorns, much to the displeasure of the passengers, who thought it unwise to announce the ship’s position while passing through a war zone with known u-boat activity.

At 10:00 AM the fog lifted, and Lusitania continued on towards Ireland in clear weather. Another submarine warning was received from the Admiralty at 11:55 AM, reading,

"SUBMARINE ACTIVE IN SOUTHERN PART OF IRISH CHANNEL, LAST HEARD OF TWENTY MILES SOUTH OF CONNINGBEG LIGHT VESSEL. MAKE CERTAIN LUSITANIA GETS THIS.”

With this notice, Captain Turner changed course toward the Old Head of Kinsale to the Northeast, in order to move closer to the coast of Ireland, and away from the reported u-boat activity.

At approximately 1:00 PM, another warning was received from Admiralty, stating a U-Boat was spotted at Cape Clear, heading west. This was a relief to Turner, as Cape Clear was 20 miles behind him, and the u-boat was heading away.

German submarine U-20, commanded by Walther Schwieger, was patrolling the waters off the coast of southern Ireland. It had already sunk the Earl of Lathom, SS Candidate, and SS Centurion in just the last two days. U-20 was short on fuel, and had only three torpedoes remaining, but Schwieger was still hopeful to get a shot at his much sought after target, the Lusitania. At 1:20 PM, glaring through his periscope, Schweiger spotted a vessel in the distance, and shouted to his pilot, “four funnels, schooner rig, upwards of 20,000 tons and making about 22 knots!” The pilot confirmed, it was either Lusitania or Mauretania, which were both listed as armed cruisers in their documentation. Schwieger then ordered U-20 to submerge to 11 meters and proceed to intercept. Five minutes later U-20 rose to periscope depth. Schwieger could still see the Lusitania, but the ship was not in line for a torpedo attack.

At 1:45 PM, Captain Turner changed course again, returning to 87 degrees, almost due east, and parallel to the Irish coast. This was exactly what Walther Schwieger had hoped. Schwieger maneuvered his vessel into position, and when Lusitania was at a distance of 700 meters, gave the order to fire one torpedo. The underwater missile hissed through the water at 38 knots at a depth of 3 meters toward the unsuspecting passenger ship, leaving a foamy wake behind it.

Seaman Leslie Morton, a lookout on Lusitania’s bow, spotted the incoming torpedo and shouted, “Torpedoes coming on the starboard side!” There was no reaction from the bridge, and Seaman Thomas Quinn again shouted from the crow’s nest, “Torpedo! Starboard side, sir!”

Crewman John O’Connell was outside, on the deck during his lunch break. He noticed the ship was steaming dead ahead, which was unusual in the war zone. Typically the ship would be sailing in a zigzag pattern as an evasive maneuver from submarines. Just then, he heard a thud, and moments later an enormous column of water shot up from the starboard side.

Commander Walther Schwieger of U-20 dictated the following into his ship’s log: 2.10pm. Clean bowshot at 700 metres range, angle of intersection 90 degrees, estimated speed 22 knots. Torpedo hits starboard side right behind the bridge. An unusually heavy detonation takes place with a very strong explosion cloud (far beyond front funnel). The explosion of the torpedo must have been followed by a second one (boiler or coal or powder?).

The Lusitania was struck by a torpedo on May 7th, 1915.